Top 3 Beginner Grant Writing Mistakes (and How to Fix Them)

About six months into my grant writing journey, I had a major humbling moment. I’d spent hours on a proposal I felt confident about—clear need statement, detailed program plan, heartfelt narrative.

A few days after submitting, the president of the foundation emailed me. His message was polite but direct:

“Please revise your application and resubmit it with supporting numbers and outcomes.”

That moment was a valuable lesson in my early career despite my initial embarrassment: great storytelling is only half the equation. Funders want—and need—proof. Data backs up your mission, validates your impact, and gives funders confidence that their dollars are going toward something measurable and meaningful.

Since then, I’ve worked with volunteers, executive directors, and other grant writers, and I’ve noticed that there are a few common mistakes many of us many early on. The good news is that every single one of them is fixable.

In this blog, I’ll walk you through the top three beginner grant writing mistakes I made, plus the simple, actionable steps to avoid them.

Mistake #1: Not Incorporating Quantiative and Qualitative Data

When that funder returned my application and asked for data, I realized I had no clue where to even begin. I had written a compelling narrative, yes, but it was based on emotion and urgency, not evidence. I wasn’t backing up my story with the kind of data funders look for to understand impact.

What Do We Mean by “Quantitative” and “Qualitative” Data?

Let’s break it down:

Quantitative data is anything you can measure with numbers. This might include:

Number of people served

Increase in test scores or attendance

Percentage of participants who achieved a goal

Dollar value of goods distributed

Qualitative data tells the story behind the numbers. This includes:

Testimonials from participants

Community feedback

Quotes from focus groups or surveys

Observations or stories from staff and volunteers

For grassroots organizations, especially those doing people-centered, community-based work, qualitative data is just as valuable as quantitative data. Together, these two types of data give funders a fuller picture of your impact.

Why Data Matters to Funders

Funders aren’t just investing in ideas—they’re investing in outcomes. They need to show their boards, stakeholders, and the public that their dollars are driving change. That’s why they look for numbers and stories that demonstrate progress, effectiveness, and alignment with their goals.

If you’re a grassroots org, the idea of “data” might feel intimidating, but you probably already have more of it than you think!

Examples of Grassroots Data Collection

Here’s what data might look like in your world:

You run a food pantry:

Quantitative: How many families you serve per week/month/year

Qualitative: A testimonial from a mother who was able to feed her kids during a layoff

You lead a youth mentorship program:

Quantitative: 90% of students improved their school attendance

Qualitative: A story about a student who build confidence through the program

You offer childbirth education:

Quantitative: 75% of participants felt more prepared for labor and delivery

Qualitative: Survey responses from parents about how the course eased their fears

How to Start Gathering This Data

If you don’t already have a system for tracking this kind of information, don’t worry! Start small and build from there:

Track your inputs, outputs, and outcomes.

Inputs: What goes into your program (staff time, dollars, supplies)

Outputs: What you do (number of classes held, meals served)

Outcomes: What changes because of your program (increased knowledge, improved well-being)

Use surveys or feedback forms.

Tools like Google Forms and other online form software, or even paper surveys after events, can help you gather both types of data.

Pro tip: Create a flyer with a QR linking to your survey or feedback form. Take it with you to events, programs, etc., so your participants can easily scan the code to access the form.

Conduct focus groups.

Invite a small group of participants to share their experiences. Record their feedback (with consent, of course) and pull out key themes or quotes.

Check in regularly.

Build in moments of reflection and data gathering throughout the year (monthly or quarterly) to track your progress.

Build a Data-Driven Culture

You don’t need to become a full-blown research team, but you do need to start thinking strategically about how you collect and use data.

Assign someone (even if it’s you) to keep tabs on data collection

Schedule quarterly program reviews using the data you’ve gathered

Ask your team, “What are we learning from this info? How can it improve our programs?”

Bonus: in many grant applications, you’ll see questions around how you listen to your community when structuring/deploying programs. Being able to point to how you use data to learn and improve will strengthen your proposals.

Free Tool: Logic Model Template

If you need a simple structure to help you start thinking through your program’s data—from what you’re doing to what you’re trying to achieve—download our free Logic Model Template. It’s the same tool I use to help organizations map out their goals, activities, and measurable outcomes.

Mistake #2: Not Researching the Funder Before Applying

Here’s something I wish I had internalized from day one: grant writing is not one-size-fits-all. Early in my career, I made the mistake of treating every grant opportunity the same. I’d skim the eligibility section, check the deadline, and jump straight into writing—without ever learning who the funder really was.

Big mistake.

Funders want to see that you understand them. That you’re aligned with their mission. That you’ve taken the time to learn what they care about, and that you’re not just sending them a copy-pasted proposal that’s been blasted to 10 other foundations.

What “Researching a Funder” Actually Means

It goes way beyond reading their homepage. When you’re researching a potential grantmaker, you should be looking for:

Their mission and values: What problems are they trying to solve? Who do they want to serve?

Their funding priorities: Are they focused on education, health equity, food insecurity, environmental justice, etc.

Geographic or population focus: Do they only fund in a certain city, county, or region? Do they prioritize certain communities, like BIPOC-led organizations, rural populations, or animal-focused programs?

Past grantees: Who have they funded in the past, and what kind of work did those organizations do?

Average grant size and type: Are they offering multi-year general operating support or one-time restricted programmatic funding?

Why This Matters—Especially If You Don’t Have a Relationship Yet

If you’re applying to a foundation for the first time, your proposal is their first impression of your organization. You want it to be clear, compelling, and customized.

Tailoring your proposal shows that you respect their priorities and that your work directly supports their goals. It also helps you avoid wasting time applying to funders who may not be a good fit in the first place.

How to Effectively Research a Funder

Here are simple, actionable ways to research potential funders before you apply:

1. Read the Full Guidelines, Not Just the Summary

Many funders will outline not just what they fund, but how they want to be approached. They may prioritize collaborative work, evaluation plans, or equity-centered initiatives.

2. Review Their IRS Form 990s

You can find a foundation’s 990 on sites like Candid, Instrumentl, or ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer. Here’s what to look for:

Who they’ve funded recently

Grant amounts

Funding trends over time

Key language or outcomes described in their giving

This can help you determine whether your request is realistic, and how to frame it.

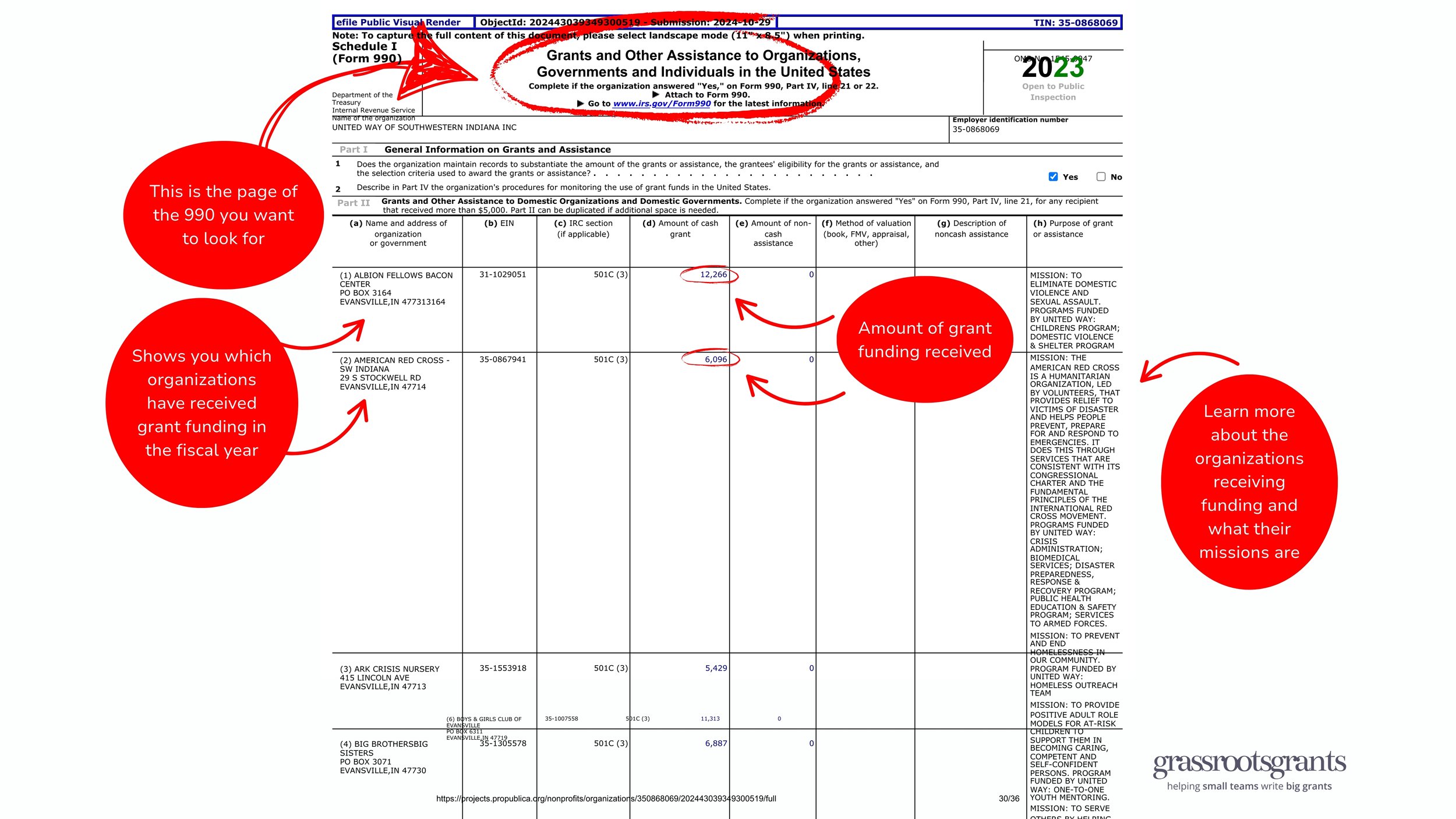

Example 990: United Way of Southwestern Indiana’s 2023 990, sourced from ProPublica. This shows which page of Form 990 you should look for (Grants and Other Assistance to Organizations, Governments and Individuals in the United States), and what you can learn from this page, including which organizations received funding in that fiscal year, what the amount of the grants were, and what programs the grants were given for.

3. Explore Annual Reports or News Releases

These documents give insight into the foundation’s current focus, recent partnerships, or shifts in strategy. Pay attention to the language they use, as you can often echo it back in your grant proposal.

4. Analyze Their Outcomes and Tie Them to Yours

Say a funder emphasizes “increasing access to prenatal care” and your org offers free doula services to low-income families. In your application, don’t just say you “support moms”—spell out exactly how your work contributes to increased access to prenatal care. Connect the dots for them.

5. When Possible, Reach Out Directly

Some foundations are open to pre-application emails or brief calls. If that’s the case, introduce yourself and ask if your program seems aligned with their priorities. In my past life as a sales rep, we used to always say “A warm lead is better than a cold one,” and that’s true for grant prospecting as well. This can also help save you time down the road by eliminating foundations that aren’t a good fit for your program.

Tip: Keep a Funder Research Tracker

Getting organized demystifies the grant process. Create a simple spreadsheet or database to track:

Who you’ve researched

Key takeaways from their 990s and website

Past deadlines and notes

Whether you’ve applied or plan to, and for what program

This will save you time and help you submit better-targeted, more competitive applications.

Mistake #3: Not Submitting Custom, Detailed Budgets

Early on, I used to think submitting my organization’s general operating budget was “good enough.” After all, it showed our income and expenses, so shouldn’t that be sufficient?

I learned the hard way that it isn’t.

Funders don’t want to fund your entire organization (unless, of course, the grant is for general operating support. But even then, they still want specifics). Most grants are program-specific, which means your budget needs to match the program you’re pitching, line by line.

Submitting a one-size-fits-all budget can come across as rushed, vague, or even lazy, and it makes it harder for reviewers to understand what exactly their funding would be supporting.

Why Custom Budgets Matter

They show you’ve thought through the details of your program

They make it easier for funders to see where their money will go

They demonstrate transparency and accountability

They allow you to ask strategically based on what the funder can realistically give

In short: a clear, tailored budget builds trust and can set you apart from competing organizations.

What a Strong Program Budget Includes

A solid grant budget isn’t just a bunch of numbers, but a story about your program told through dollars. It should reflect what it really takes to deliver the impact you’re promising in your narrative.

Here’s what your grant proposal budget should include:

Line Items

Here are some examples of line items that might be in your budget:

Personnel: staff time, salaries, benefits, contractors

Supplies & materials: everything from office printer paper to PPE

Travel or transportation: gas mileage, public transit passes, delivery costs

Facilities or space rental: if you hold workshops or events

Evaluation: tools or consultants to measure your impact

Communications or outreach: flyers, paid ads, website costs

Break It Down

Use clear labels and be as detailed as possible. For example, instead of “supplies,” write, “Activity kits for youth workshop (50 kits @ $10 each)”

Include units when possible, as this helps funders understand quantity and cost

Don’t forget in-kind support or match funding if the grant requires it

Requested vs. Total Cost

Show what portion of the program, you’re asking the funder to cover. For example, in the same row you’d have a column for the line item, a column for the total cost, and a column for the request from funder.

This approach signals that you’re leveraging multiple sources of support and that you understand how to stretch their dollars wisely.

Tailoring Budgets for Each Funder

Even if you’re running the same program, different funders have different preferences. Some might love to fund staff time. Others prefer to pay for direct services or materials. Some might shy away from covering indirect costs altogether.

By customizing your budget and aligning it with what the funder wants to support (based on their guidelines, conversations, or 990s), you increase your chances of success.

And whatever you do, make sure the budget aligns with your proposal narrative. If you mention a new initiative, make sure the costs for launching it are in your numbers. If you highlight community partnerships, include the stipends or any in-kind donations.

Free Tool: Grant Budget Template

Need help getting started? Download our free Grant Budget Template—a plug-and-play spreadsheet designed with grassroots nonprofits in mind. It walks you through the exact line items, descriptions, and calculations you need to build a strong, funder-ready budget.

Mistakes Are Part of the Process,

If you’ve made any of these mistakes, you’re not alone. I’ve made them too, and I still catch myself learning and adjusting with every single application I write.

Grant writing is a skill that sharpens over time. And just like building a successful program, becoming a stronger grant writer is about learning from feedback, reflecting on what didn’t work, and constantly looking for ways to improve.

To recap:

Use both quantitative and qualitative data to back up your story and show impact

Research your funders like you’re preparing for a job interview. Understand what they value and how your work aligns

Always submit a custom, detailed budget that clearly communicates what you’re asking for and why

Whether you’re part of a scrappy grassroots team or a growing nonprofit, these small but might shifts can make a big difference in how funders perceive your application, and in your ability to secure the support your community deserves.

And remember, you don’t have to figure it all out alone!

We’ve got free tools to help you build stronger proposals:

Download our Logic Model Template to start thinking through your program’s goals, activities, and outcomes

Grab our Grant Budget Template to build a transparent, funder-aligned budget you can be proud of